In part one we already arrived at some useful formulations of the moral law that illustrate its transcendental but obviously factual nature even better than the more famous formulations of the categorical imperative.

In this final part we will elaborate on Kant’s concept of holiness and how he connects that with human dignity and the moral law. We will further look at what can be the function of the knowledge of Kant’s analysis of morality in this day and age.

All quotes are from the following three translations:

-Immanuel Kant, Critique of Pure Reason, translated by P. Guyer and A.W. Wood (Cambridge University Press 1998). I use the abbreviation “CPR” to reference this work.

-Immanuel Kant, Groundwork of the Metaphysics of Morals, translated by M. Gregor (Cambridge University Press 1998). I use the abbreviation “gw” to reference this work.

-Immanuel Kant, Critique of Practical Reason, translated by M. Gregor (Cambridge University Press 2015). I use the abbreviation “KpV” to reference this work.

A holy law for every common understanding, a worth that can compensate us for the loss of everything that provides a worth to our condition.

...do you demand then that a cognition that pertains to all human beings should surpass common understanding and be revealed to you only by philosophers? The very thing that you criticize is the best confirmation of the correctness of the assertions that have been made hitherto, that is, that it reveals what one could not have foreseen in the beginning, namely that in what concerns all human beings without exception nature is not to be blamed for any partiality in the distribution of its gifts, and in regard to the essential ends of human nature even the highest philosophy cannot advance further than the guidance that nature has also conferred on the most common understanding.

(CPR A831-B859)

In part one we saw that the principle of morality stems straight from the awareness of being a singular reasonable being so it’s obvious that any common understanding has the moral law within itself. The purpose of Kant’s work in this is not to instruct the common understanding about what the moral law is, but to instruct the not so common understanding about what it is not. Namely that it has nothing to do with an elaborate knowledge of the world, quite the contrary.

Beware of the fact that Kant can be a bit confusing in this quote by using the word “human nature” in a more general colloquial sense while in his preceding analysis (and through most of the Critique of Pure Reason) he uses “nature” strictly as that which is governed by mechanistic laws of nature and logical laws of thought.

The moral law is holy (inviolable). A human being is indeed unholy enough but the humanity in his person must be holy to him. In the whole of creation everything one wants and over which one has any power can also be used merely as a means; a human being alone, and with him every rational creature, is an end in itself: by virtue of the autonomy of his freedom he is the subject of the moral law, which is holy.

(KpV 5:87)

The only thing that is truly whole and singular in itself and as such presents itself to us is the awareness of the singular reasonable being within ourselves. The moral law is a formulation of the possibility of this singular “I” willing freely and apart from anything empirical. Kant’s understanding of holiness thus is a holiness from within and not a holiness that reveals itself from the world outside. The only thing the world has to offer is heteronomy and is in contradiction with holiness.

...a worth that can compensate us for the loss of everything that provides a worth to our condition...

(gw 4:450)

This holiness from within is truly a worth that is capable of compensating any loss of empirical worth, even if this loss is so devastating and caused by attempts to completely destroy one’s dignity, this inner moral worth can survive. There are plenty of examples and testimonies in human history that illustrate this.

...the utmost that finite practical reason can effect is to make sure of this unending progress of one’s maxims toward this model and of their constancy in continual progress, that is, virtue; and virtue itself, in turn, at least as a naturally acquired ability, can never be completed, because assurance in such a case never becomes apodictic certainty and, as persuasion, is very dangerous.

(KpV 5:33)

A willing that is absolutely free is a requirement for a singular being and thus must be regarded at least as a possibility. But that willing, although it has the ability to determine our faculty of choice, doesn’t have a determined object of experience in the real empirical world. If it would have, it would just abide by the natural law of cause and effect. So any depiction of any kind of completion of the moral law as an object of experience must be looked at with great distrust because its reality would contradict a singular being with self consciousness.

What is to be done in accordance with the principle of the autonomy of choice is seen quite easily and without hesitation by the most common understanding; what is to be done on the presupposition of heteronomy of choice is difficult to see and requires knowledge of the world; in other words, what duty is, is plain of itself to everyone, but what brings true lasting advantage, if this is to extend to the whole of one’s existence, is always veiled in impenetrable obscurity, and much prudence is required to adapt the practical rule in accordance with it to the ends of life even tolerably, by making appropriate exceptions. But the moral law commands compliance from everyone, and indeed the most exact compliance. Appraising what is to be done in accordance with it must, therefore, not be so difficult that the most common and unpracticed understanding should not know how to go about it, even without worldly prudence.

(KpV 5:36)

Let us compare here on the one hand the most common understanding, gifted with very limited intellectual capacities with on the other hand a highly intellectual understanding which is capable of foreseeing lots of possible consequences of his actions (maybe he’s a scholar in ethics). When they are both presented with a moral issue in which they have to decide which action is the morally right thing to do, the only difference between the two will be that the first has less oversight of all the possible consequences of his action. The second will have more oversight of possible consequences of his action but the moral principle that determines their will in taking action is exactly the same in both cases. Moreover while the scholar might have the impression that he’s better capable of foreseeing more consequences and thus capable of a better moral decision, he must admit he can’t foresee all the consequences of his action as time will progress and in the end his action is as potentially disastrous (or even more disastrous) for human kind as the action of the common man.

When looking at human history it could even be said that most of mankind’s self inflicted disasters are caused by those who had the impression to foresee the most consequence of their actions and acted accordingly to an idea they thought was possible to complete with certainty in this world.

This of course doesn’t mean that we should not consider the consequences of our action, on the contrary. We ought to do so each in our own capacity but it is obvious that the more we foresee possible consequences, the more indeed we see a potential increase in possibly good outcome, but at the same time a potential increase in possible bad outcome and also an increase in uncertainty of outcome.

Happiness

The practical law from the motive of happiness I call pragmatic (rule of prudence); but that which is such that it has no other motive than the worthiness to be happy I call moral (moral law)! The first advises us what to do if we want to partake of happiness; the second commands how we should behave in order even to be worthy of happiness.

(CPR A806-B834)

Now this is what I call a rule that is ready for daily use! Very quotable and readily understandable Kant here!

The principle of one’s own happiness, however much understanding and reason may be used in it, still contains no determining ground for the will other than such as is suitable to the lower faculty of desire; and thus either there is no higher faculty of desire at all or else pure reason must be practical of itself and alone, that is, it must be able to determine the will by the mere form of a practical rule without presupposing any feeling and hence without any representation of the agreeable or disagreeable as the matter of the faculty of desire, which is always an empirical condition of principles. Then only, insofar as reason of itself (not in the service of the inclinations) determines the will, is reason a true higher faculty of desire, to which the pathologically determinable is subordinate, and then only is reason really, and indeed specifically, distinct from the latter, so that even the least admixture of the latter’s impulses infringes upon its strength and superiority, just as anything at all empirical as a condition in a mathematical demonstration degrades and destroys its dignity and force. In a practical law reason determines the will immediately, not by means of an intervening feeling of pleasure or displeasure, not even in this law; and that it can as pure reason be practical is what alone makes it possible for it to be lawgiving.

(KpV 5:24,25)

That is to say, where each has to put his happiness comes down to the particular feeling of pleasure and displeasure in each and, even within one and the same subject, to needs that differ as this feeling changes; and a law that is subjectively necessary (as a law of nature) is thus objectively a very contingent practical principle, which can and must be very different in different subjects, and hence can never yield a law because, in the desire for happiness, it is not the form of lawfulness that counts but simply the matter, namely whether I am to expect satisfaction from following the law, and how much. Principles of self-love can indeed contain universal rules of skill (for finding means to one’s purposes), but in that case they are only theoretical principles (such as, e.g.,how someone who would like to eat bread has to construct a mill). But practical precepts based on them can never be universal because the determining ground of the faculty of desire is based on the feeling of pleasure or displeasure, which can never be assumed to be universally directed to the same objects.

(KpV 5:25,26)

The principle of happiness can indeed furnish maxims, but never such as would be fit for laws of the will, even if universal happiness were made the object. For, because cognition of this rests on sheer data of experience, each judgement about it depending very much upon the opinion of each which is itself very changeable, it can indeed give general rules but never universal rules, that is, it can give rules that on the average are most often correct but not rules that must hold always and necessarily; hence no practical laws can be based on it.

(KpV 5:36)

To satisfy the categorical command of morality is within everyone’s power at all times; to satisfy the empirically conditioned precept of happiness is but seldom possible and is far from being possible for everyone even with respect to only a single purpose.

(KpV 5:37)

For this reason, again, morals is not properly the doctrine of how we are to make ourselves happy but of how we are to become worthy of happiness. Only if religion is added to it does there also enter the hope of some day participating in happiness to the degree that we have been intent upon not being unworthy of it.

(KpV 5:130)

None of the above quotes need much clarifying because they fit in nicely with all that was said before. The reason I find them very much worth to mention is that in modern society happiness plays a role in morals that is very opposed to Kant’s ideas. In today’s society happiness in itself is often regarded moral duty number one and thus failure to be happy is often seen as a moral failure. I think this idea of happiness almost completely taking the place of moral worth can have devastating effects on mental health. And to be clear it’s not the idea that happiness is good that is doing the damage (happiness is of course very good, and Kant agrees with that) but the idea that happiness as an object of experience can function as a determination of a free will and can yield a practical moral law can only result in total moral confusion and frustration that can further lead to far worse conditions then the mere feeling of unhappiness.

Kant first demonstrates that happiness in itself doesn’t even have what it takes in the first place to determine a will freely and second he makes it very clear and obvious that even if it would be the case that happiness should be that what determines our free will, it is absolutely impossible to predict and foresee what action will bring happiness and thus happiness is completely dependent on factors that are outside our will.

So if we indeed want to rescue the idea of freedom of will we should categorically say: our free will is not at all capable to will happiness (not a-priori and also not a-posteriori) and thus should not be bothered by that impossible task.

BUT for all you fortune seekers, don’t worry too much:

To assure one's own happiness is a duty (at least indirectly); for, want of satisfaction with one's condition, under pressure from many anxieties and amid unsatisfied needs, could easily become a great temptation to transgression of duty.

(gw 4:399)

And for all you unfortunate unhappy people, don’t worry either because if your unhappiness doesn’t become a transgression of duty, there’s no reason your inner moral worth should in any way be regarded as less than that of a happy person. And people who claim that they know what to do in order to become happy are clearly wrong, even some ancients already knew that.

The upside of this overwhelming emphasis on happiness of today’s society is that it can provide us with a useful introspective inquiry into the moral law. For most people probably can’t imagine willing anything other then happiness. But if we where to dig even deeper beyond that willing of happiness we must admit this willing is maybe not entirely free and still dependent on empirical conditions and we must ask ourselves two questions:

Is it possible to freely will something good other than happiness?

And if so, what would that be?

If we are truly moral beings, the answer to that first question must clearly be: yes, I can clearly and obviously freely want something that is something other than happiness and that is also good and I recognize that willing to be the only principle that determines my moral worth.

The answer to the second question is less obvious and for today’s fortune seekers may be a bit underwhelming or disappointing in Kant’s analysis because so it seems we simply arrive at merely the form of volition as such and indeed as autonomy. A simple fact of reason that just points at the inherent worth of a singular reasonable being. And indeed the critics are right, in the completion of his analysis Kant doesn’t arrive at yet another loaded, emotionally heavy concept which we can decorate with symbols of a lavish world. Instead he arrives at something light, empty, pure and incorruptible. For some thinkers this is such an unbearable concept that even in their interpretation of Kant they try to pervert this simple concept and search for holiness in heteronomy, which is so obviously a contradiction.

And yet again we arrive at a point where the function of Kant’s critical project becomes clear as primarily a negative function. Not to learn what morality is, because that was known from the start by the most common understanding but to unlearn what it is not. The unsustainable and unlawful premises of radical empiricism or materialism are simply not sufficient when they are confronted with the task of analyzing concepts like morality and reason or even humanity for that matter. This radical empiricism or materialism renders the analysis of those concepts impossible and forces itself into an unavoidable dogmatic symbolism again and again across the whole spectrum of worldviews regardless if these worldviews are theistic, deistic, agnostic or atheistic.

The idea of self consciousness from the perspective of a radical empiricist or materialist remains something of a mystery and depending on his state of mind can vary from “an illusion” or a “construct” to “something empirical science is yet to unravel for sure”. From that standpoint indeed there is a lot to unlearn and to separate. And at the end of that process the idea of a “kingdom of ends” surprisingly regains its obvious and non controversial ontological truth.

Kingdom of ends vs nature

Duty and what is owed are the only names that we must give to our relation to the moral law. We are indeed lawgiving members of a kingdom of morals possible through freedom and represented to us by practical reason for our respect; but we are at the same time subjects in it, not its sovereign, and to fail to recognize our inferior position as creatures and to deny from self-conceit the authority of the holy law is already to defect from it in spirit, even though the letter of the law is fulfilled.

(KpV 5:82,83)

The majesty of duty has nothing to do with the enjoyment of life; it has its own law and also its own court, and even though one might want to shake both of them together thoroughly, so as to give them blended, like medicine, to the sick soul, they soon separate of themselves; if they do not, the former will effect nothing at all, and though physical life might gain some force, the moral life would fade away irrecoverably.

(KpV 5:89)

One could say the difficult and almost impossible task of any court of law across the world apart from presenting the facts is to separate rigorously on the one hand the world of enjoyment of life (and its counterpart: the world of misfortune in life), which has its own rights and demands leniency, from on the other hand the world of moral duty. Not to deny one or the other, but to protect the concepts that form humanity. Human dignity has no legitimacy when a singular reasonable being cannot be held accountable for wrongdoings as well as for acts of good will. Often a verdict and a sentence in a court of law has the peculiar effect of not only restoring the dignity of the victim but also and even more so of the accused. That effect is the real function of a court of law instead of correcting or trying to erase or even prevent wrongdoings. And indeed these courts of law have two roots of sufficient reason and an overarching principle: on the one hand an elaborate knowledge of the world and on the other hand, tho moral law within ourselves and the imperative to separate the two.

And just in this lies the paradox that the mere dignity of humanity as rational nature, without any other end or advantage to be attained by it - hence respect for a mere idea - is yet to serve as an inflexible precept of the will, and that it is just in this independence of maxims from all such incentives that their sublimity consists, and the worthiness of every rational subject to be a lawgiving member in the kingdom of ends; for otherwise he would have to be represented only as subject to the natural law of his needs.

(gw 4:439)

Now, a human being really finds in himself a capacity by which he distinguishes himself from all other things, even from himself insofar as he is affected by objects, and that is reason.

(gw 4:452)

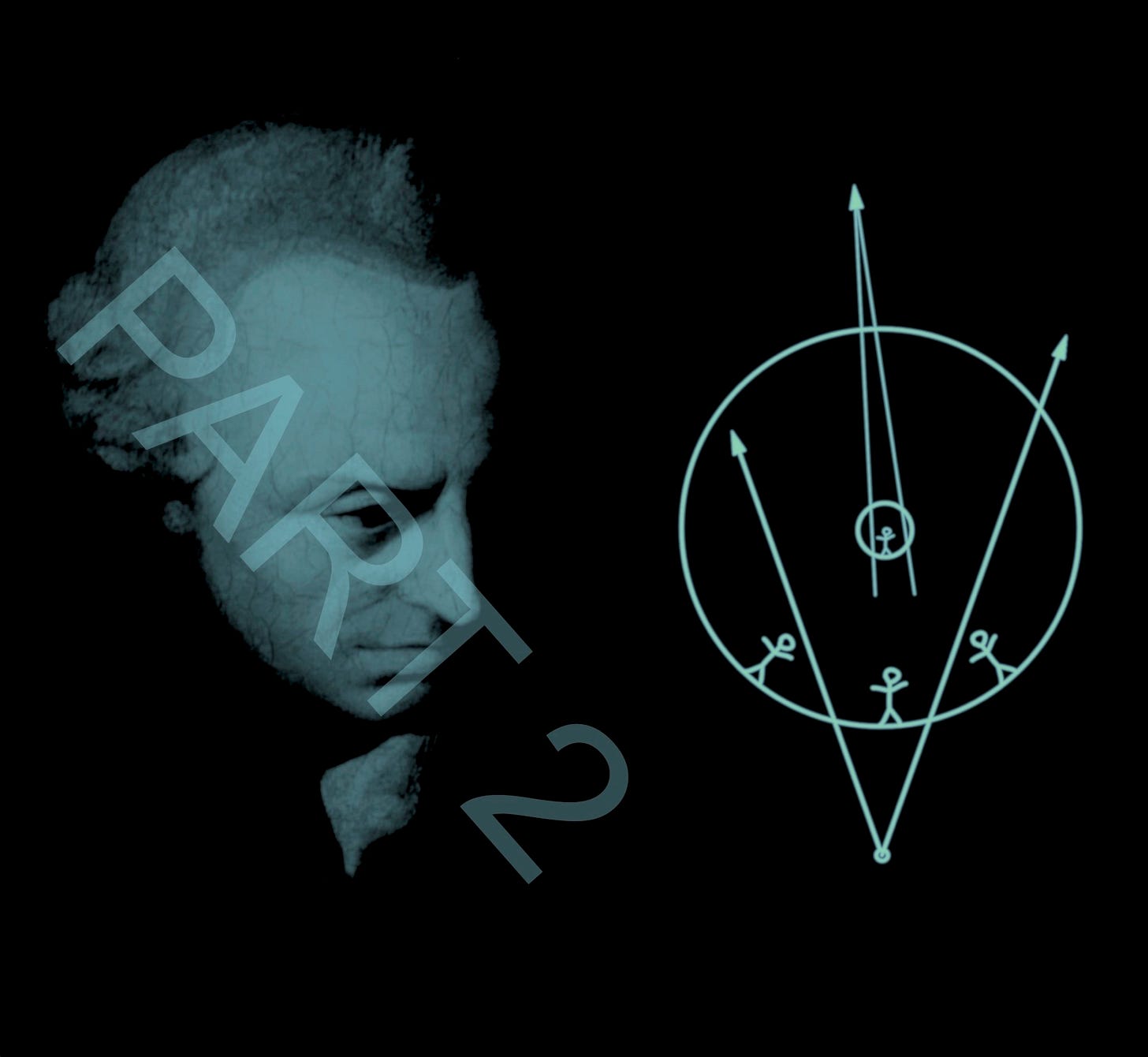

Because of this a rational being must regard himself as intelligence (hence not from the side of his lower powers) as belonging not to the world of sense but to the world of understanding; hence he has two standpoints from which he can regard himself and cognize laws for the use of his powers and consequently for all his actions; first, insofar as he belongs to the world of sense, under laws of nature (heteronomy); second, as belonging to the intelligible world, under laws which, being independent of nature, are not empirical but grounded merely in reason.

As a rational being, and thus as a being belonging to the intelligible world, the human being can never think of the causality of his own will otherwise than under the idea of freedom;

(gw 4:452)

And so categorical imperatives are possible by this: that the idea of freedom makes me a member of an intelligible world and consequently, if I were only this, all my actions would always be in conformity with the autonomy of the will; but since at the same time I intuit myself as a member of the world of sense, they ought to be in conformity with it; and this categorical ought represents a synthetic proposition a priori, since to my will affected by sensible desires there is added the idea of the same will but belonging to the world of the understanding - a will pure and practical of itself, which contains the supreme condition, in accordance with reason, of the former will; this is roughly like the way in which concepts of the understanding, which by themselves signify nothing but lawful form in general, are added to intuitions of the world of sense and thereby make possible synthetic propositions a priori on which all cognition of a nature rests.

(gw 4:454)

The human being, who this way regards himself as an intelligence, thereby puts himself in a different order of things and in a relation to determining grounds of an altogether different kind when he thinks of himself as an intelligence endowed with a will, and consequently with causality, than when he perceives himself as a phenomenon in the world of sense (as he also really is) and subjects his causality to external determination in accordance with laws of nature. Now he soon becomes aware that both can take place at the same time, and indeed must do so. For, that a thing in appearance (belonging to the world of sense) is subject to certain laws from which as a thing or a being in itself it is independent contains not the least contradiction...

(gw 4:457)

And thus the contemporary naturalist, radical empiricist or materialist must find himself in some kind of highly confused state when it comes to morality and self consciousness because when he analyses his premises (which serve a legitimate purpose on their own) they contradict the core concepts that constitute his own being and it doesn’t take long to see that no resolving of the matter is ahead, neither by means of reasoning nor by empirical research. This confused state nevertheless doesn’t need to last long because when he looks around him he sees the reassuring reality of humanity doing its thing as a kingdom of ends with the sole purpose of confirming human dignity, no matter the difficulties it encounters. A kingdom of ends that is obvious for any reasonable human being. After all this unlearning he doesn’t even have to reject his premises, because they serve their own purpose, namely gaining elaborate knowledge of the world, which is the important task of science (a task which Kant holds dear to his heart). What the naturalist needed to unlearn though is that science, by its own premises, is not capable of separating the moral law from the world of cause and effect.

God as an inevitable a-priori afterthought

The impossible word play in the above title and the fact that I didn’t mention God once until now might seem a bit unfair because Kant unmistakably is a self declared and proud theist which in his own words means he “believes in a living God”. On the other hand it is also clear that in his critical project, God seems to function only as a concluding concept; not as a starting point and not even as a necessary key component (I would argue). In his moral philosophy simply said this comes down to “morality first” and “God second”. And even that is a bit generous because the amount of deduction that has taken place in his whole critical theory from the moment of the Cartesian “I think therefore I am” until we arrive at a God-concept isn’t exactly straight forward like one plus one equals two. And although his deduction in my eyes is indeed very convincing and leads to a legitimate, useful and beautiful awe-inspiring God-concept, the question may rise how the common understanding justifies a legitimate and unshakable faith in a living God and an afterlife? Well, he does indeed provide some kind of justification for that but this comprehensive guide isn’t the place to evaluate that aspect of Kantian theology.

This however is the place to conclude Kant’s deduction of morality with a catchphrase that in my view sums up Kant's moral philosophy and that would be “I think therefore I am...moral”. It reflects the Cartesian starting point which Kant indeed accepts and the way he deduces his whole moral theory from it.

So the concluding quotes of my selection are just to illustrate indeed Kant’s emphasis on the secondary nature of God in his analysis of morality. Just keep in mind these quotes are not representative of Kant’s whole theology and philosophy of religion. These aspects of Kant’s philosophy deserve introductory guides on their own.

Even the Holy One of the Gospel must first be compared with our ideal of moral perfection before he is cognized as such; even he says of himself: why do you call me (whom you see) good? none is good (the archetype of the good) but God only (whom you do not see).

(gw 4:408)

So far as practical reason has the right to lead us, we will not hold actions to be obligatory because they are God's commands, but will rather regard them as divine commands because we are internally obligated to them.

…

Moral theology is therefore only of immanent use, namely for fulfilling our vocation here in the world by fitting into the system of all ends, not for fanatically or even impiously abandoning the guidance of a morally legislative reason in the good course of life in order to connect it immediately to the idea of the highest being, which would provide a transcendental use but which even so, like the use of mere speculation, must pervert and frustrate the ultimate ends of reason.

(CPR A819-B847)

But love for God as inclination (pathological love) is impossible, for he is not an object of the senses.

(KpV 5:83)

But if practical reason were to fetch in addition an object of the will, that is, a motive, from the world of understanding, then it would overstep its bounds and pretend to be cognizant of something of which it knows nothing.

(gw 4:458)

It now follows of itself that in the order of ends the human being (and with him every rational being) is an end in itself, that is, can never be used merely as a means by anyone (not even by God) without being at the same time himself an end, and that humanity in our person must, accordingly, be holy to ourselves: for he is the subject of the moral law and so of that which is holy in itself, on account of which and in agreement with which alone can anything be called holy.

(KpV 5:131,132)

©Mathias Mas, 2025.

One practical question that remains to be answered is how can we determine whether instances of our ‘will’ (our choices/intentions) are ‘free’ Vs. being only a consequence of the natural world, therefore deterministic, therefore not free but an expression of external forces that move us and of tendencies that merely ‘happen’ to us.

I suggest that choices that result from deliberation, made on the basis of consistent reasoning are, to a degree, free, whereas choices for which we have no clear reason are deterministic. Choices are perfectly free only if our reasons are perfectly consistent with the world as we know it, including our self-ideation within it.