Kant’s Moral Philosophy: a comprehensive introductory guide PART 1

Nature vs respect for an empty formal law

Introduction:

When Kant’s moral philosophy is mentioned in the mainstream intellectual space, and even in the space of quite serious contemporary and less contemporary philosophy, more often than not two aspects of it seem to pop up. Usually the first thing that happens is a quotation of one of the formulations of Kant’s categorical imperative and with it, the implicit notion that this formulation is somehow the keystone, the holy grail, the final result of Kant’s labour presented to us as a finished product, ready for daily use. By quoting a formulation of the categorical imperative as a starting point; the contemporary thinker in question exposes himself as someone who probably didn’t go through the labour resulting in that formulation. The reason being these short formulations of the categorical imperative are highly misleading in understanding Kant’s theory and even might lead you to an understanding of Kant’s theory that is the exact opposite of what it is supposed to say. Although they might be correct formulations of said imperative, the even more correct formulation would be the sum total of all of Kant’s theoretical critical work about morals minus his short formulations of the categorical imperative. And thus pointing at key points of that sum total would be much more appropriate as an introduction to Kantian morality.

A second aspect that often gets mentioned is Kant’s notoriously bad use of examples. If this mention is indeed a pointing towards the examples being very bad, then it is a correct assessment of that aspect, because Kant’s use of examples is indeed problematic. If it is simply a mention of one of Kant’s bad examples that is supposed to illustrate the failure of the categorical imperative as a useful guideline in moral issues, then again you can be certain that the author of this ingenious refutation of Kant’s moral theory didn’t bother to do serious research. Kant gives numerous inspiring heartwarming examples that very adequately illustrate certain aspects of his moral theory but unfortunately he also gives some examples that seem to illustrate the exact opposite of what his theory says and indeed seem to refute his own ideas. It’s as if Kant deliberately didn’t give examples of particularly these aspects of his theory that are impossible to illustrate but his publisher afterwards made up some quick examples to fill in the blancs. For someone who thoroughly studies Kant’s philosophy, his use of extremely bad examples mixed with excellent examples is a bit of a mystery. After all, Kant himself says:

Nor could one give worse advice to morality than by wanting to derive it from examples.

(gw 4:408)

A more general and deeper complaint that thinkers seem to have when criticizing Kant’s critical theory as a whole is that when Kant analyses certain concepts into its parts, there seems to be nothing left in these parts that refers to the original concept. Which of course is a sign of the incredible thoroughness of Kant’s analysis rather then a weak point. If one is to analyze concepts like “knowledge”, “morality”, “the good will”, “freedom of will” one shouldn’t be surprised the emotional load of these concepts is nowhere to be found in its parts and thus it’s quite pointless to mourn over it. Philosophers who postulate yet another “meaning content” in the parts of their analysis aren’t exactly clarifying things and have yet to understand what “meaning” means. (these are the type of Philosophers who feel the need to wiggle their fingers in the air while mentioning loaded concepts in the hope to sprinkle some magic significance over their own ego)

The core of Kant’s moral philosophy is an integral part of his complete ontological-epistemological system and is spread out over three works. In the Critique of Pure Reason (1781) Kant already establishes a great part of his moral theory by analyzing the concepts of freedom and freedom of will versus the mechanistic nature of the whole of all appearances, which he calls “nature” and what in contemporary philosophy and science would be called “empirical reality”. Also the idea that the “moral law” should abstract from inclinations is already present in the Critique of Pure reason. In Groundwork of the Metaphysics of Morals (1785) and Critique of Practical Reason (1788) he further develops the moral law in his broader framework of the idea of “reason” namely what it should be and what it should not be if we are to hold the premise of freedom of will.

In this comprehensive guide I will present quotes from the above mentioned three works in a more or less thematic order and give clarifying comments on them. My main purpose is to highlight key-aspects of Kant’s moral theory that mostly get no attention in a mainstream space.

All quotes I used are from the following three translations:

-Immanuel Kant, Critique of Pure Reason, translated by P. Guyer and A.W. Wood (Cambridge University Press 1998). I use the abbreviation “CPR” to reference this work.

-Immanuel Kant, Groundwork of the Metaphysics of Morals, translated by M. Gregor (Cambridge University Press 1998). I use the abbreviation “gw” to reference this work.

-Immanuel Kant, Critique of Practical Reason, translated by M. Gregor (Cambridge University Press 2015). I use the abbreviation “KpV” to reference this work.

Let’s jump right in!

Nature vs freedom of will

In respect of what happens, one can think of causality in only two ways: either according to nature or from freedom. The first is the connection of a state with a preceding one in the world of sense upon which that state follows according to a rule. Now since the causality of appearances rests on temporal conditions, and the preceding state, if it always existed, could not have produced any effect that first arose in time, the causality of the cause of what happens or arises has also arisen, and according to the principle of understanding it in turn needs a cause.

(CPR A532-B560)

By freedom in the cosmological sense, on the contrary, I understand the faculty of beginning a state from itself, the causality of which does not in turn stand under another cause determining it in time in accordance with the law of nature. Freedom in this signification is a pure transcendental idea, which, first, contains nothing borrowed from experience, and second, the object of which also cannot be given determinately in any experience, because it is a universal law - even of the possibility of all experience - that everything that happens must have a cause, and hence that the causality of the cause, as itself having happened or arisen, must in turn have a cause; through this law, then, the entire field of experience, however far it may reach, is transformed into the sum total of mere nature.

(CPR A533-B561)

Like I said earlier, “nature” in this context is what in contemporary science would be called “the real empirical world” that is knowable by the laws of nature/laws of logical thought. Kant emphasizes these laws of thought in this concept of nature over a more ontological (or metaphysical) meaning of nature and thus “nature” becomes “the field of experience”/ “the world of sense”. An “object” in this empirical world is for Kant a mere “object of experience”, no more and no less. In this mechanistic world of cause and effect, the idea of freedom from this world of sense is an impossibility. If I would try to fit this idea of freedom (of will) into this world, according to the rules of this world, there is absolutely now way I would succeed. It would be as if an act of freedom would be something that pops into existence from nowhere, some sort of absolute spontaneity, coming from nowhere. It should also be clear that if freedom nevertheless would survive as a valid concept, there could never be a law of nature that can demonstrate freedom. Kant is very clear in that matter.

Since the knowable world of cause and effect is determined by time one could argue that any concept that is singular and persistent in time is already a breach from that empirical world of cause and effect. In the same sense a being that in some capacity has the ability to “wait” is already dangerously close to a complete breach from nature. A singular being in a condition of “waiting” aka setting his whole organism in some kind of hold, outside of time is not a particularly difficult thing to understand but if we would try to express this specific condition within the framework of natural deterministic laws, we would bring ourselves in great difficulty.

Another example to demonstrate the possibility of a concept that has validity outside time is the persistent subject or the logical “I am”. That is the centre of logical thought and without which there is no “object of experience” possible. In order for a thought of any object to be possible in any way, we have to assume a singular “I” that is persistent in time at least for the duration of the formation of that thought. This logic incorruptibility of the subject is persistent in time. No matter the empirical damage brought to my organism, as long as my self consciousness is intact, the persistent subject is one and the same in it’s function of perceiving objects. That’s why we don’t hold an empirical organism accountable for its actions but rather the persisting singular transcendental subject (= the “I am”). We assume this subject to be persistent in time while its empirical organism at no point in time stays the same.

Freedom in the practical sense is the independence of the power of choice from necessitation by impulses of sensibility. For a power of choice is sensible insofar as it is pathologically affected (through moving-causes of sensibility); it is called an animal power of choice (arbitrium brutum) if it can be pathologically necessitated. The human power of choice is indeed an arbitrium sensitivum, yet not brutum! but liberum, because sensibility does not render its action necessary, but in the human being there is a faculty of determining oneself from oneself, independently of necessitation by sensible impulses.

(CPR A534-B562)

“Practical” for Kant is all that can provide the power of choice the elements that can direct us to this or that choice. A principle is called practical if it helps us in making a choice of any kind. If all my practical principles are just a matter of fitting into the rules of cause and effect, I’m not free and I just react to the empirical impulses with an effect that abides a natural law.

“Pathological” for Kant is any choice of action that is caused by empirical impulses alone. In contemporary colloquial terms “pathological” would not include all actions caused by empirical impulses as such but only those actions that have a harmful effect to our physical or mental health. This might seem a radical use of terms from Kant’s side but it must be noted that Kant doesn’t necessarily understand every “pathologically affected” action to be harmful or connected to the contemporary notion of “disease” or “unhealthiness”. Kant in no way propagates a deprivation of sensory pleasure as a healthy thing to do.

...thus the difficulty we encounter in the question about nature and freedom is only whether freedom is possible anywhere at all, and if it is, whether it can exist together with the universality of the natural law of causality, hence whether it is a correct disjunctive proposition that every effect in the world must arise either from nature or freedom, or whether instead both, each in a different relation, might be able to take place simultaneously in one and the same occurrence. The correctness of the principle of the thoroughgoing connection of all occurrences in the world of sense according to invariable natural laws is already confirmed as a principle of the transcendental analytic and will suffer no violation. Thus the only question is whether, despite this, in regard to the very same effect that is determined by nature, freedom might not also take place, or is this entirely excluded through that inviolable rule? And here the common but deceptive presupposition of the absolute reality of appearance immediately shows its disadvantageous influence for confusing reason.

(CPR A536-B564)

Will is a kind of causality of living beings insofar as they are rational, and freedom would be that property of such causality that it can be efficient independently of alien causes determining it, just as natural necessity is the property of the causality of all non-rational beings to be determined to activity by the influence of alien causes.

(gw 4:445)

And thus the proposition “I’m free to do whatever I want” doesn’t represent true freedom of will in the Kantian sense because if my wants are handed to me by nature, there’s nothing free about them and they just abide the laws of cause and effect. A more suited proposition, in line with Kant’s idea of freedom of will would be “I’m free to want that which is unimaginable in the natural world of cause and effect”. If the wanting in the second proposition is indeed possible, maybe that is more suited to be called truly free and even could be called “moral”.

If, therefore, freedom of the will is presupposed, morality together with its principle follows from it by mere analysis of its concept.

(gw 4:447)

In other words and in the opposite direction: If only the natural world of cause and effect has validity, the concept of morality would only yield mere descriptions of the peculiarities of the natural inclinations.

All human beings think of themselves as having free will.

(gw 4:455)

On the other side, it is equally necessary that everything which takes place should be determined without exception in accordance with laws of nature; and this natural necessity is also no concept of experience, just because it brings with it the concept of necessity and hence of an a priori cognition.

(gw 4:455)

At this point it should be clear that Kant in no way wants to give up on the concept of nature on the one hand or freedom of will on the other hand; although they clearly seem to contradict each other. Reason seems to instruct us not to cancel out one concept in favor of the other but also not to mix them together carelessly.

Both concepts need further analysis so we can gain even more clarity in what separates them and with this clarity these concepts might even gain more validity once their thorough analysis is complete.

Object of desire vs respect for the moral law in itself

All practical principles that presuppose an object (matter) of the faculty of desire as the determining ground of the will are, without exception, empirical and can furnish no practical laws. By “the matter of the faculty of desire” I understand an object whose reality is desired. Now, when desire for this object precedes the practical rule and is the condition of its becoming a principle, then I say (first) that this principle is in that case always empirical. For, the determining ground of choice is then the representation of an object and that relation of the representation to the subject by which the faculty of desire is determined to realize the object. Such a relation to the subject, however, is called pleasure in the reality of an object. This would therefore have to be presupposed as a condition of the possibility of the determination of choice. But it cannot be cognized a priori of any representation of an object, whatever it may be, whether it will be connected with pleasure or displeasure or be indifferent. Hence in such a case the determining ground of choice must always be empirical, and so too must be the practical material principle that presupposes it as a condition.

(KpV 5:21)

It is surprising that men, otherwise acute, believe they can find a distinction between the lower and the higher faculty of desire according to whether the representations that are connected with the feeling of pleasure have their origin in the senses or in the understanding. For when one inquires about the determining grounds of desire and puts them in the agreeableness expected from something or other, it does not matter at all where the representation of this pleasing object comes from but only how much it pleases. If a representation, even though it may have its seat and origin in the understanding, can determine choice only by presupposing a feeling of pleasure in the subject, its being a determining ground of choice is wholly dependent upon the nature of inner sense, namely that this can be agreeably affected by the representation. However dissimilar representations of objects may be – they may be representations of the understanding or even of reason, in contrast to representations of sense – the feeling of pleasure by which alone they properly constitute the determining ground of the will (the agreeableness, the gratification expected from the object, which impels activity to produce it) is nevertheless of one and the same kind not only insofar as it can always be cognized only empirically but also insofar as it affects one and the same vital force that is manifested in the faculty of desire, and in this respect can differ only in degree from any other determining ground.

(KpV 5:23)

Whether I want a cookie, a satisfaction of my sexual desires or the realization of world peace and happiness for all beings, if the reality of these objects is desired because of the pleasure or gratification they may give me, for Kant they are still just objects of the lower faculty of desire and still belong to the realm of cause and effect.

Consequently, respect for the moral law is a feeling that is produced by an intellectual ground, and this feeling is the only one that we can cognize completely a priori and the necessity of which we can have insight into.

(KpV 5:73)

But it is a feeling which is directed only to the practical and which depends on the representation of a law only as to its form and not on account of any object of the law; thus it cannot be reckoned either as enjoyment or as pain, and yet it produces an interest in compliance with the law which we call moral interest, just as the capacity to take such an interest in the law (or respect for the moral law itself) is the moral feeling properly speaking.

(KpV 5:80)

In the above two quotes Kant comes dangerously close to contradicting himself because elsewhere he very much advocates against “feelings” as a legitimate source for true moral determination of the will. Respect for the moral law however is a special kind of feeling that is completely a priori and has no source in the empirical world. Stricto sensu, a feeling would be always empirical (sensory) but indeed in this case “respect for the moral law” should be regarded as predating any empirical feeling. We could even regard “respect for the law” as the source or transcendental model for all other sensory feeling if we allow ourselves a radical interpretation. In this radical interpretation we can assume any self consciousness to be moral per definition.

At this point the moral law begins to take shape as a result of the inquiry into the possibility of a practical principle that doesn’t need pleasure in the realization of an empirical object of experience. To be clear it is not at all an aversion of pleasure that leads Kant to this way of looking at the moral law but simply the fact that pleasure requires knowledge of the reality of the desired object and can never result in an unconditional law that governs any free will a-priori.

Only an empty formal law can bring forth an immediate a-priori good will.

We shall thus have to investigate entirely a priori the possibility of a categorical imperative, since we do not here have the advantage of its reality being given in experience, so that the possibility would be necessary not to establish it but merely to explain it.

(gw 4:420)

When I think of a hypothetical imperative in general I do not know beforehand what it will contain; I do not know this until I am given the condition. But when I think of a categorical imperative I know at once what it contains. For, since the imperative contains, beyond the law, only the necessity that the maxim be in conformity with this law, while the law contains no condition to which it would be limited, nothing is left with which the maxim of action is to conform but the universality of a law as such; and this conformity alone is what the imperative properly represents as necessary. There is, therefore, only a single categorical imperative and it is this:

act only in accordance with that maxim through which you can at the same time will that it become a universal law.

(gw 4:420, 421)

An absolutely good will, whose principle must be a categorical imperative, will therefore, indeterminate with respect to all objects, contain merely the form of volition as such and indeed as autonomy

(gw 4:444)

So it seems that the moral law governing an absolutely good will actually only consists of the formulation of the possibility of a moral law that doesn’t require any knowledge of the empirical world. I would argue that Kant’s above formulation is already a better formulation of the categorical imperative than his more famous ones. The moral law is simply a formulation of the mere “form of volition as such and indeed as autonomy”

It is therefore the moral law, of which we become immediately conscious (as soon as we draw up maxims of the will for ourselves), that first offers itself to us and, inasmuch as reason presents it as a determining ground not to be outweighed by any sensible conditions and indeed quite independent of them, leads directly to the concept of freedom.

(KpV 5:29)

A reasonable being doesn’t need to learn the moral law. The moral law is an immediate consequence of a reasonable self-consciousness. That’s the reason why we fearlessly approach other reasonable beings. At this point it should be clear that the moral law is not at all some kind of clever rule Kant came up with to help us in our day to day moral dilemma’s; quite the contrary it just points at it’s self evidence, simplicity and logical function in the concept of freedom.

Fundamental law of pure practical reason: So act that the maxim of your will could always hold at the same time as a principle in a giving of universal law.

(KpV 5:30)

Reading this famous formulation of the categorical imperative in isolation can give the wrong impression that the required universality is a mere arbitrary rule. Why should it be universal? Why is this in any way a better law than a law that just maximizes pleasure for all beings?

Because the universality in this law is a mere consequence of the fact that this law has to be a-priori for it to be able to determine the will, free of consequence. So this universality requirement is not at all because we think the consequences of universality are better then the consequences of maximal pleasure. The law is universal because only a universal law points at a will that is free from empirical determination and thus belonging to a singular subject that is accountable for its actions.

A second wrong impression this formulation gives is the idea that Kant has thought long and hard about the world and human kind with all its flaws and wrongdoings and in order to fix all that Kant wants us to act in a certain way. And although some of his examples may strengthen this impression of a prescriptive, almost arbitrary dogmatic nature of his moral law, it’s not hard to find a completely different impression in the quotes I’m presenting here. An impression that simply points at a thorough analysis of the concept of freedom.

We could even state that Kant’s moral law is the exact opposite of a golden rule to fix problems in the real world or even to judge consequences.

It is here a question only of the determination of the will and of the determining ground of its maxims as a free will, not of its result. For, provided that the will conforms to the law of pure reason, then its power in execution may be as it may, and a nature may or may not actually arise in accordance with these maxims of giving law for a possible nature; the Critique which investigates whether and how reason can be practical, that is, whether and how it can determine the will immediately, does not trouble itself with this.

(KpV 5:46)

In other words: no trolley problem can distract the moral law from its function, namely the immediate determination of the free will, regardless of its consequences. Trolley problems are set up to maximize the gravity of two different consequences while minimizing the perceived moral difference between the two consequences. They are a study of consequences, not of morality.

Any trolley problem can be replaced by the mother of all trolley problems namely: imagine a trolley set up for 2 directions; one direction lets the trolley kill 10 million people and the other direction lets the trolley kill, well ….. also 10 million people. The result is the same but nevertheless it will feel like a moral dilemma because the proposed action points at YOU as a singular person that has a free will. And so it’s not the consequences that makes matters of moral importance but the simple fact of reason that the moral law is capable of determining a free will.

The moral thing to do when you encounter a trolley problem in real life is to run far away of course.

A good will is not good because of what it effects or accomplishes, because of its fitness to attain some proposed end, but only because of its volition, that is, it is good in itself and, regarded for itself, is to be valued incomparably higher than all that could merely be brought about by it in favor of some inclination and indeed, if you will, of the sum of all inclinations. Even if, by a special disfavor of fortune or by the austere provision of a stepmotherly nature, this will should wholly lack the capacity to carry out its purpose - if with its greatest efforts it should yet achieve nothing and only the good will were left (not, of course, as a mere wish but as the summoning of all means insofar as they are in our control) - then, like a jewel, it would still shine by itself, as something that has its full worth in itself. Usefulness or fruitlessness can neither add anything to this worth nor take anything away from it. Its usefulness would be, as it were, only the setting to enable us to handle it more conveniently in ordinary commerce or to attract to it the attention of those who are not yet expert enough, but not to recommend it to experts or to determine its worth.

(gw 4:394)

To be truthful from duty, however, is something entirely different from being truthful from anxiety about detrimental results, since in the first case the concept of the action in itself already contains a law for me while in the second I must first look about elsewhere to see what effects on me might be combined with it.

(gw 4:402)

I do not, therefore, need any penetrating acuteness to see what I have to do in order that my volition be morally good.

(gw 4:403)

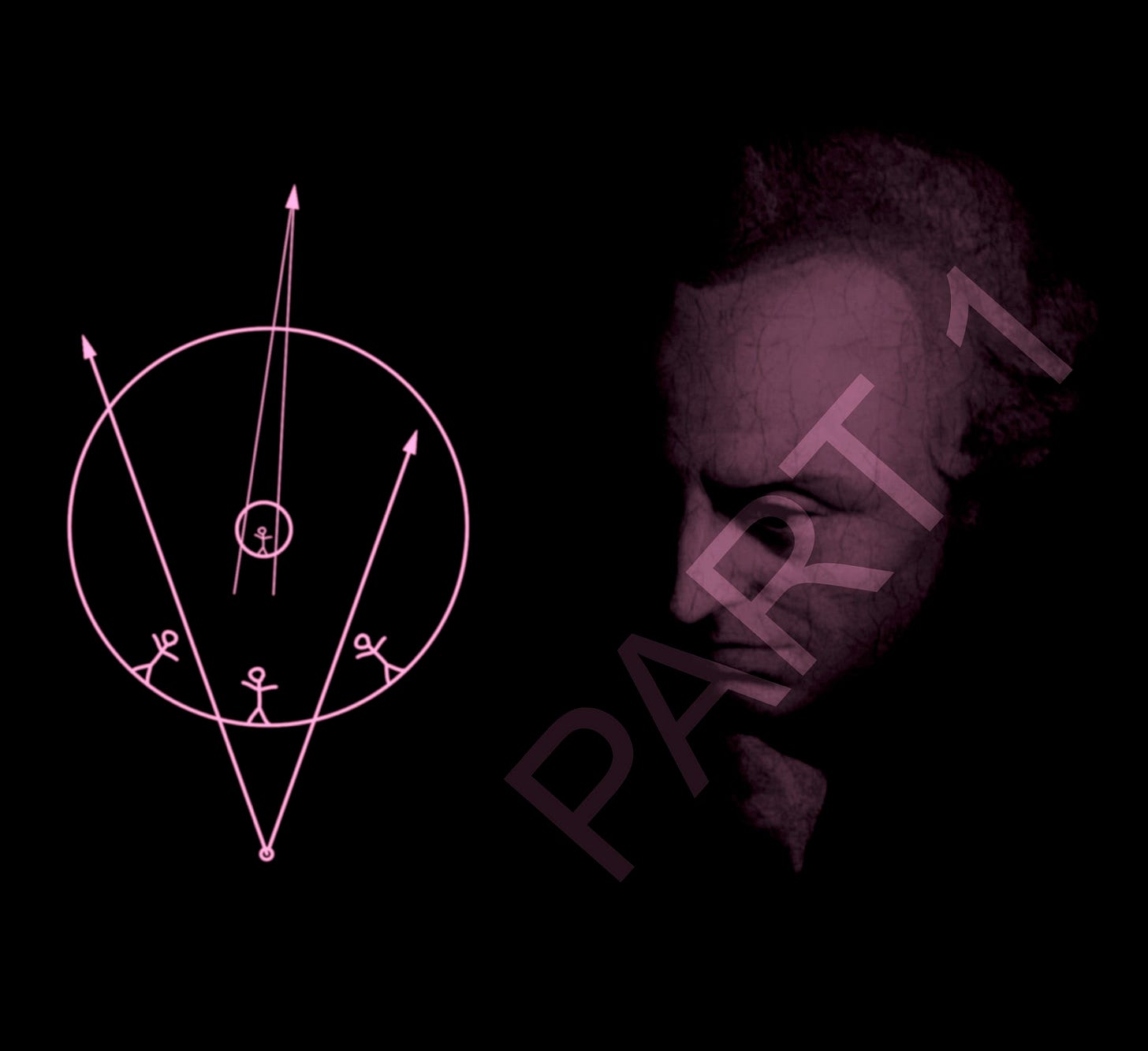

I conclude with an image that is perhaps best suited to depict Kant’s moral law which is indeed the image of a person with a good will, regardless the consequences. A person with a good will in a sense is a naive person. Naive towards the possible harmful natural inclinations of the person he or she approaches but also naive towards his or her own harmful inclinations towards the other. It’s a good will a-priori, before calculation of the consequences. In an other sense it can also be not at all naïve, approaching the other person with the knowledge the consequences can be potentially disastrous but nevertheless a state of an empty a-priori good will is very consciously demanded by my faculty of reason, not because the consequences of that good will are expected to be better but because any other kind of will is in contradiction with a self awareness as a singular being and thus with humanity.

In the second and final part of this comprehensive guide I will elaborate on:

-Kant’s idea of holiness and how it relates to his moral law.

-How happiness should and should not play a role in the determination of our free will.

-A looking back at “nature vs free will” from the perspective of the “kingdom of ends”.

-And finally where God does (or does not) fit in all this.

©Mathias Mas, 2025.

To summarise this, the moral law is universal a priori, as a matter of logical consistency, which is synonymous with conscious rationality, and it necessitates acting consistently with all manifestations of conscious rationality (other conscious rational beings, or simply Humanity). Yes?

This was incredibly fascinating! I have always found Kant’s notion of Respect baffling but now I think I get it. Especially with the first comment above— that really shed some light as well